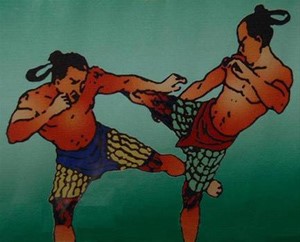

As he undertook to gain widespread credibility and acceptance across stylistic, racial/ethnic and class lines, U Ba Than organized the traditionally brutal and savage indigenous Bando Boxing, in an attempt to make it safer and to reduce injuries and fatalities. At that time in the early post-World War II period, Bando Boxing was not yet “Westernized”. The Thais, however, proved less resistant to change and fairly readily westernized Muay Thai.

U Ba Than Gyi’s son, Maung Gyi (Dr. M. Gyi), was a participant in these bouts. These brutal experiences made an indelible impression on Dr. Gyi. To this day, he insists that Bando be highly effective in combat.

U Ba Than Gyi’s son, Maung Gyi (Dr. M. Gyi), was a participant in these bouts. These brutal experiences made an indelible impression on Dr. Gyi. To this day, he insists that Bando be highly effective in combat.

Reviving Bando Boxing was a critical way to establish credibility for U Ba Than Gyi with the “underground” martial arts culture. His involvement in the Military Athletic Club and his force of personality all combined to uniquely qualify U Ba Than Gyi as the man who could elicit the essence of the underground systems from the remaining masters.

One enormous problem facing U Ba Than Gyi was the difficulty encountered in resurrecting and reviving systems without offending the holders of the knowledge. A keen political balancing act was needed to satisfy the demands of surviving “traditional” masters, heads of family systems, various monk sects and ethnic groups. Thus, as U Ba Than traveled the country and contacted a growing network of such persons, he interviewed them and gained their confidence gradually.

As he began to perceive the nature of what had been driven underground, U Ba Than Gyi concluded that a real part of the Burmese culture had been threatened with extinction. In Burma, the martial artist lived as a critical part of the society. Not only could one punch and kick, but was a kind of “Renaissance Man” or “Renaissance Woman”.

The Burmese martial artist was, traditionally, in addition to being a repository of knowledge concerning methods of harming or killing the individual, a repository of knowledge concerning health and healing. Frequently, martial artists were indigenous medical practitioners to whom the community turned for treatment from illness and injury. Moreover, the martial artist in Burmese society was sought after by the populace for his or her understanding of nature, animals, plants, the elements, geography, language and customs, as well as historical fact and cultural traditions. Frequently, because of their advantages in these areas, they were called upon to act as arbitrators of disputes, or as judges. Thus, the Burmese martial artist, prior to the British suppression of the arts, had served in a highly respected position in the society. Therefore, the presence of the martial artist in a community or in a given situation, was the presence of a person of wisdom (a physician, herbologist, scholar, warrior, philosopher, jurist) and was the symbolic infusion of great power and justice into a community environment or an inter-personal or inter-group transaction.

Recognizing this, U Ba Than Gyi gave these surviving masters the deference they deserved, and asked that they share with him, for posterity, their knowledge. The reaction to Gyi’s shrewd and genuine inquiries was outstanding; some 200 masters met with him, taught him and demonstrated their methods, disclosing the history and context of their heritage.