When Dr. Gyi first came to America he had no intention of teaching Bando. Rather, he came to the U.S. for an education and was grooming himself to work for the Foreign Service, the diplomatic corps or some international agency. Bando was the last thing on his mind. However, during the 1950s and 1960s, there were several youth gangs and civil unrest in Washington, D.C. These gangs roamed around the city, very often, attacking and robbing foreign diplomats, tourists, government workers and senior citizens. The D.C. police were unable to stop them completely. On three separate occasions, within one year, members of three different gangs attacked Dr. Gyi. The attackers were young, arrogant and undisciplined. Fortunately, Dr. Gyi survived their attacks with only minor cuts and bruises. In return, he was more generous with his “gifts.” He gave them broken bones, dislocations of joints and lacerations on their faces, but restrained himself from delivering any lethal blows.

When Dr. Gyi first came to America he had no intention of teaching Bando. Rather, he came to the U.S. for an education and was grooming himself to work for the Foreign Service, the diplomatic corps or some international agency. Bando was the last thing on his mind. However, during the 1950s and 1960s, there were several youth gangs and civil unrest in Washington, D.C. These gangs roamed around the city, very often, attacking and robbing foreign diplomats, tourists, government workers and senior citizens. The D.C. police were unable to stop them completely. On three separate occasions, within one year, members of three different gangs attacked Dr. Gyi. The attackers were young, arrogant and undisciplined. Fortunately, Dr. Gyi survived their attacks with only minor cuts and bruises. In return, he was more generous with his “gifts.” He gave them broken bones, dislocations of joints and lacerations on their faces, but restrained himself from delivering any lethal blows.

After these events Dr. Gyi was never challenged or attacked by these gangs again. Shortly thereafter, though, the gang leaders asked him to teach them some of his tricks. After they agreed to his strict conditions, Dr. Gyi began training them in some of the basic Bando techniques at a city park in NW Washington. With assistance from one young police officer that was previously trained as a social worker, Dr. Gyi was able to bring some order and discipline into his Bando sessions.

The first stage in the development of Bando in America in the 50s and 60s was to gain recognition and acceptance by major martial arts leaders from the Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Okinawa karate masters. Bando then was the only martial arts system from Southeast Asia officially taught at a major university in the United States. At that time there was a strong attitude among various martial arts communities that the “true” systems came from Japan, China, Korea and Okinawa. Systems from Southeast Asia were considered to be “illegitimate,” inferior,” “outsider’s art,” “primitive,” and “not true system.”

Dr. Gyi recalls, “I was very much alone in that environment. I was a very small fish swimming in the ocean with giant sharks. I had serious doubts regarding my survival in the martial arts world. At The American University, I had to modify my curriculum several times to adjust to the highly competitive martial arts culture. Very often I asked myself, “How can this little fish swim along side of the giant sharks without being eaten?”

Dr. Gyi recalls, “I was very much alone in that environment. I was a very small fish swimming in the ocean with giant sharks. I had serious doubts regarding my survival in the martial arts world. At The American University, I had to modify my curriculum several times to adjust to the highly competitive martial arts culture. Very often I asked myself, “How can this little fish swim along side of the giant sharks without being eaten?”

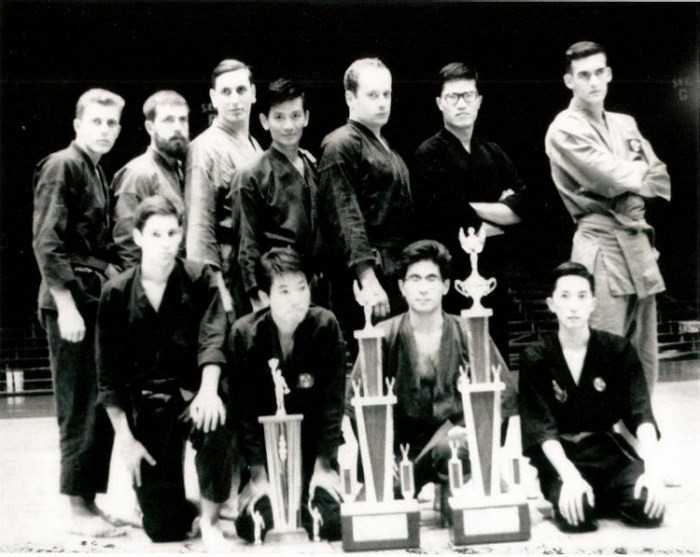

Within a year or two of rigorous training, Bando fighters such as Hugh McHugh, Joe Manley, Lloyd Davis, Bob Maxwell, Mark Bjishkian, Geoff Willcher and many others became confident and skillful enough to face the fighters from other systems. They performed extremely well in various major Japanese karate, Korean karate, Okinawa karate and Chinese Kung Fu tournaments. These men served as the foundation of the American Bando Association and are considered the “First Generation”. They helped to gain recognition from leaders and practitioners of other martial arts communities in this country. These small fish had become barracudas in the sea, confidently swimming along side of the giant whales and great sharks.

The second stage of development of Bando in America was to form a private and non-profit organization with 3 defined goals:

Organizational Goal #1

As Burma was a major battlefield in Southeast Asia during WWII, Dr. Gyi’s father and other elders felt that it was most appropriate to honor the Allied veterans of China-Burma-India Theater of war and other theaters of war in Asia.

Organizational Goal #2

Similarly, the second goal is to preserve the combative and martial arts systems practiced in the CBI Theater of WWII.

During the Burma Campaign from1942 to 1946, soldiers from many nations were involved. There were British, Americans, Chinese, Indians, Gurkhas, West Africans, Japanese, Koreans, Okinawans and Manchurians. There were also Burmese, Kachins, Chins, Shans, Mons, Arakanese and other tribesmen. Many battles fought in both northern and southern Burma involved jungle warfare and close-quarter hand-to-hand fighting. Burma became the testing ground for many of the combative arts of the Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Gurkhas, Burmese, Kachins, Karens and other tribes. There was active exchange of martial techniques at various training camps and among various troops and tribes. These techniques were incorporated into the Bando System taught today in the U.S.

Organizational Goal #3

The third goal is to promote cross-cultural exchange and to share knowledge with other martial arts systems.

Many Bando tournaments, seminars and clinics are open to other systems. Bando practitioners participate in numerous karate tournaments sponsored by Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Okinawan and other systems. Bando instructors are encouraged to promote cross-cultural exchange of knowledge about sports and martial arts. Dr. Gyi feels that Bando in America must be an open system and not a closed one. Members can grow from new experiences through interaction with practitioners of other systems.

In 1968, with the help of Dr. Marc Lewis, Joe Manley, Lloyd Davis, Robert Maxwell, Dr. Robert Hill, Dr. Paul Kwan and others, the American Bando Association was officially established. The ABA has become one of the longest ongoing private, non-profit martial arts organizations in the United States. It is the only martial arts organization that honors the veterans of the China-Burma-India Theater of WWII.

The 3rd stage in the development of Bando was to cultivate and nurture the Bando practitioners with knowledge, skills and commitment to the system. Again, with the help of Dr. Gyi’s father and other elders, he was able to translate and formulate the principles of 9 animal systems, 9 staff systems and 9 sword systems. These Dhoe, Dhot and Dha systems became the curriculum foundation of the Bando system in America and are still taught in the same way today.

It is important to note, Dr. Gyi has never had any intention of promoting the Bando system to become one of the dominant systems in the United States. He believes there are hundreds of successful commercial schools, teaching various forms of Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Okinawa and Brazilian martial arts systems. Dr. Gyi feels that “commercialization of the system based on a profit making motive” would affect the way we view and teach Bando in America. His intention has always been to maintain the status of the ABA as a private, non-profit martial arts organization to honor the Allied veterans of China-Burma-India Theater of WWII and to encourage cross-cultural exchange of ideas and activities with members of other systems.